The global financial system is built on a paradox: governments must maintain stability and growth through spending, but the way they finance these expenditures often erodes the very system they are trying to uphold. The United States, as the world's largest economy, perfectly embodies this dilemma. With the federal deficit projected to reach $2 trillion annually, the U.S. Treasury relies heavily on issuing debt to meet its obligations. However, who buys this debt and the mechanisms by which they finance these purchases have profound implications for the money supply, asset prices, and the future of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

At the heart of this dynamic is the structure of political incentives. As former BitMEX CEO Arthur Hayes argued, politicians are "hard-coded" to prefer debt over taxes because spending is popular while taxation is unpopular. This preference for debt-financed spending creates a cycle where governments must constantly find buyers for their bonds. When traditional buyers—foreign central banks, commercial banks, and the private sector—are unable or unwilling to absorb these debts, the Federal Reserve intervenes as lender of last resort. This process, often disguised as "implicit quantitative easing," expands the money supply and fuels asset inflation.

This environment is particularly favorable for Bitcoin. As a decentralized asset with a fixed total supply of 21 million coins, Bitcoin stands in stark contrast to the unlimited expansion of fiat currency. For example, the US M2 money supply has grown from $12 trillion in 2015 to over $22 trillion in 2025, highlighting the continued depreciation of the dollar. Against this backdrop, Bitcoin serves as both a hedge against inflation and a bet on the sustainability of the current financial system. This article draws on the perspectives of economists and market analysts, along with the latest data, to explore the complex relationship between US debt, money printing, and the future trajectory of Bitcoin.

The Political Economy of Debt: Why Governments Prefer Printing Money to Taxing

The structure of political incentives ensures that debt is the default tool for government financing. Elected officials prioritize short-term gains—such as voter support and re-election—rather than long-term fiscal sustainability. Because the benefits of spending are immediate, while the costs of debt are deferred, politicians are incentivized to borrow rather than tax. As Hayes points out, "Politicians always tend to borrow into the future to secure their current re-election because when the bill comes due, they are likely no longer in office."

This tendency is exacerbated during periods of economic uncertainty or crisis. For example, the Trump administration extended the 2017 tax cuts, reducing government revenue while maintaining spending levels. Similarly, discussions surrounding stimulus measures, such as reviving mortgage giants like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, reflect a preference for injecting liquidity into the economy rather than implementing fiscal discipline. The result is widening deficits that must be financed through debt issuance, creating a feedback loop where the government becomes increasingly reliant on borrowing.

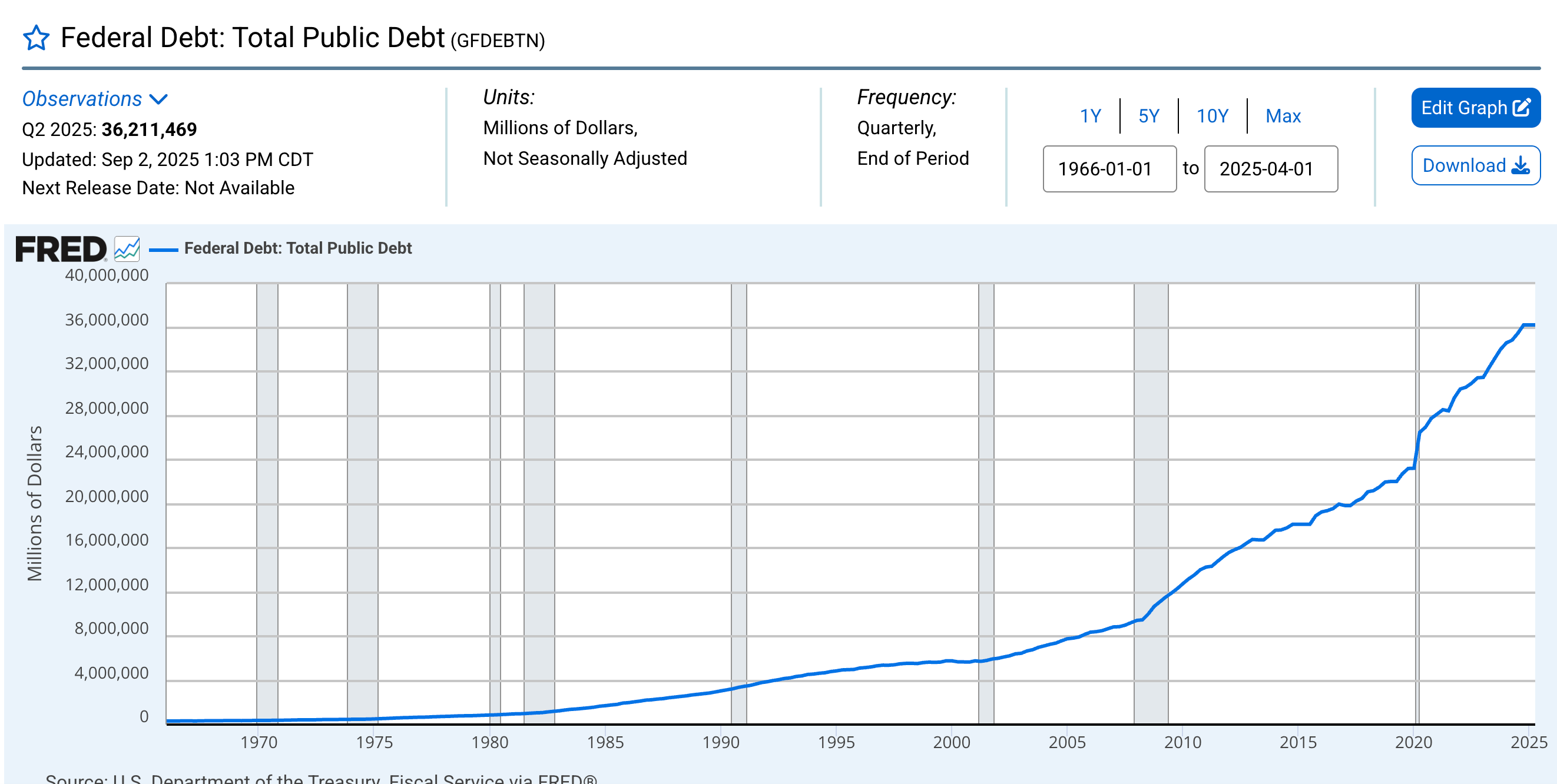

US debt chart. Source: Federal Reserve

This approach has two consequences. First, it shifts the burden of today's spending to future generations. Second, it forces the Federal Reserve to meet the Treasury's borrowing needs through indirect means, such as the Standing Repurchase Facility (SRF) or quantitative easing (QE). While these actions may have a stabilizing effect in the short term, they dilute the value of the dollar and amplify systemic risks.

What is Quantitative Easing?

Quantitative easing (QE) is an unconventional monetary policy. Simply put, it involves a central bank "printing money" to massively purchase assets such as government bonds, injecting a large amount of liquidity into the market to stimulate the economy. The goal of QE is to increase the money supply and lower interest rates by injecting funds into banks, enabling them to offer credit to businesses and consumers at more attractive rates. This credit can help businesses expand, help entrepreneurs achieve their dreams, and help consumers own homes. Once the economy recovers, the Federal Reserve will end QE by selling the securities back into the market.

To understand QE, you must first understand the central bank's conventional weapon: interest rates.

-

When the economy is sluggish, the central bank will lower interest rates to make it easier and cheaper for businesses and individuals to borrow money, thereby encouraging consumption and investment and stimulating the economy.

-

When the economy overheats and inflation is high, the central bank will raise interest rates to increase the cost of borrowing money and cool down the economy.

However, this tool has a limit: when interest rates have already fallen to zero (or near zero), central banks can no longer stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates. This situation is known as a "liquidity trap" or the "zero lower bound."

Quantitative easing (QE) operates entirely differently from traditional interest rate control: it shifts from controlling prices (interest rates) to controlling quantity (the money supply). Instead of printing money like the government, the central bank creates new electronic money (base money) out of thin air in electronic accounts. This process is called "ex nihilo" (creating something from nothing). The central bank uses this newly created money to purchase large amounts of financial assets from commercial banks and other financial institutions, primarily government bonds, but sometimes also corporate bonds and even stocks. Through these asset purchases, the central bank transfers huge sums of money to commercial banks. This leads to a significant increase in reserves within the banking system.

However, quantitative easing is only effective when banks are willing to lend and potential borrowers are willing to take the risk, which is not always guaranteed in times of uncertainty. Another potential risk of quantitative easing is that lowering interest rates often exacerbates inflation, leading to higher raw material costs for businesses, which are then passed on to consumers, thus driving up the cost of living.

Who is Buying US Debt?

The sustainability of U.S. debt depends on its availability to buyers. Historically, foreign central banks and commercial banks have been the primary purchasers of U.S. Treasury bonds. However, recent trends indicate declining demand from these traditional sources.

Foreign central banks: Geopolitical risks, such as the freezing of Russian assets, have made foreign central banks cautious about holding US debt. Instead, many central banks are diversifying their gold holdings, as evidenced by the surge in gold prices following the invasion of Ukraine.

Commercial banks: While banks continue to purchase government bonds, their capacity is limited by regulatory constraints and declining reserve balances. In fiscal year 2025, the four major money center banks purchased only $300 billion of the $1.992 trillion in issued government bonds.

Private sector: The personal savings rate in 2024 is 4.6%—lower than the federal deficit as a percentage of GDP of 6%—meaning the private sector cannot be a marginal buyer.

The gaps left by these entities have been filled by relative value (RV) hedge funds, particularly those based in the Cayman Islands. From 2022 to 2024, these funds net purchased $1.2 trillion in Treasury bonds, absorbing 37% of net bond issuance. These funds employ a leveraged strategy: buying Treasury bonds while simultaneously selling Treasury futures to capture small price differences. To execute this trade, they rely on short-term financing in the repurchase market, using their newly purchased bonds as collateral to obtain overnight cash loans.

Repurchase Market and Implicit Quantitative Easing

The Standing Repurchase Facility (SRF) is a "standing emergency funding window" set up by the Federal Reserve. It allows eligible financial institutions (mainly banks and dealers) to pledge their holdings of U.S. Treasury securities or other eligible collateral to the Federal Reserve in exchange for short-term (usually overnight) cash loans when they need cash.

The Standing Repurchase Facility (SRF) sets a ceiling on short-term interest rates by providing a reliable, collateral-based lending facility. In today's environment of high US fiscal deficits and massive Treasury bond issuance, the use of the SRF effectively serves as a hidden but crucial channel connecting the Treasury's debt issuance needs with the creation of dollar liquidity, making it an indispensable part of understanding the micro-mechanisms of "debt monetization."

| STANDING REPO FACILITY PARAMETERS |

| Operation Type: |

Morning |

Afternoon |

| Schedule: |

Every business day from 8:15 to 8:30 a.m. ET, unless otherwise stated |

Every business day from 1:30 to 1:45 p.m. ET, unless otherwise stated |

| Aggregate operation limit: |

$500 billion |

$500 billion less the accepted amount from the morning operation |

| Proposition limit: |

Two propositions per eligible security type per auction, subject to a $20 billion per proposition limit |

| Minimum bid rate: |

4.00 percent |

| Settlement: |

Same-day settled. Bank of New York (BNY) tri-party repo conventions apply. Funds will typically be delivered within thirty minutes following the operation close time. |

Same-day settled. BNY tri-party repo conventions apply. |

| Eligible counterparties: |

Primary dealers and SRF counterparties, which include depository institutions |

| Eligible securities: |

U.S. Treasuries, agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities (for additional details on the security types see Repo Securities Schedule) |

SRF operational parameters. Source: New York Fed

The repurchase agreement (repo) market has become central to dollar creation. RV funds rely on it to finance their purchases of Treasury bonds, but the

market's stability depends on the availability of cash . Traditionally, cash is provided by money market funds (MMFs) and commercial banks. However, recent developments have disrupted this balance:

Money market funds (MMFs) have shifted their investments from the repo market to short-term Treasury bills, attracted by the higher yields. This has drained cash from the repo market.

Commercial banks face their own limitations. Since the Federal Reserve began quantitative tightening (QT) in 2022, bank reserves have shrunk by trillions of dollars, reducing their lending capacity in the repurchase market.

As demand for cash increases from RV funds and private supply decreases, the Federal Reserve must intervene to prevent the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) from surging above its target range. The Fed's primary tool for this is the Standing Repurchase Facility (SRF), which allows eligible institutions to borrow cash from the Fed by pledging Treasury securities as collateral. The SRF acts as a safety valve, providing unlimited liquidity at the Fed's capped policy rate.

When the SRF is used aggressively, it is effectively equivalent to "implicit QE." Unlike traditional QE, which involves large-scale asset purchases, the SRF injects liquidity indirectly through the repurchase market. This allows the Federal Reserve to expand the money supply even without a clear policy shift. As Hayes explains, "If the SRF balance is above zero, we know the Fed is cashing in the checks politicians are writing with the money it's printing."

The difference between SRF and quantitative easing (QE)

| Characteristics |

Standing Repurchase Facility (SRF) |

Quantitative Easing (QE) |

| Operation Direction |

Standing Repurchase Facility (SRF) |

Purchases and permanently holds assets from the market and provides cash to the market |

| Balance Sheet Impact |

Temporary, short-term expansion (due to overnight lending) |

Permanent, long-term expansion |

| Central Bank Role |

Lender (accepting collateral) |

Buyer (directly purchasing assets) |

| Policy Nature |

Liquidity management tool aimed at maintaining market stability |

Monetary stimulus tool aimed at stimulating the economy and inflation |

| Collateral/Asset Destination |

Collateral is redeemed by borrowers later |

Assets are held by the Federal Reserve long-term until maturity |

How the Federal Reserve Manipulates Short-term Interest Rates?

The Federal Reserve has two policy rates: the upper limit and the lower limit of the federal funds rate; currently, they are 4.00% and 3.75%, respectively. To enforce the real short-term interest rate (SOFR, the secured overnight funding rate) within this range, the Fed uses the following tools (listed in ascending order of interest rate):

Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (RRP): Money market funds (MMFs) and commercial banks deposit cash here overnight to earn interest paid by the Federal Reserve. Reward Rate: The lower bound of the federal funds rate.

Interest on Excess Reserves (IORB): Commercial banks earn interest on excess reserves held by them at the Federal Reserve. Incentive Rate: Between upper and lower limits.

Standing Repurchase Facility (SRF): When cash is tight, it allows commercial banks and other financial institutions to pledge eligible securities (mainly U.S. Treasury bonds) and receive cash from the Federal Reserve. In essence, the Fed prints money and exchanges it for pledged securities. Reward Rate: The upper limit of the federal funds rate.

The relationship among the three:

Federal Funds Rate Lower Bound = RRP < IORB < SRF = Federal Funds Rate Upper Bound

The SOFR (Secured Overnight Funding Rate) is the Federal Reserve's target rate, representing the composite rate of various repurchase agreements. If the SOFR trades above the federal funds rate ceiling, it indicates a systemic cash crunch, which could trigger major problems. Once cash is tight, the SOFR will spike, and the highly leveraged fiat currency financial system will cease to function. This is because if buyers and sellers of marginal liquidity cannot roll over their liabilities near the predictable federal funds rate, they will suffer huge losses and stop providing liquidity to the system. No one will buy US Treasury bonds because they cannot obtain cheap leverage, leaving the US government unable to finance at an affordable cost.

Bitcoin as the Ultimate Beneficiary

The relationship between US debt issuance, money printing, and the value of Bitcoin is direct:

as the money supply expands, the purchasing power of fiat currency decreases, making scarce assets like Bitcoin more attractive . This dynamic is reinforced by several factors:

Fixed Supply: The Bitcoin protocol limits its supply to 21 million coins, a stark contrast to the ever-expanding supply of the US dollar. Between 2015 and 2025, the US M2 money supply is projected to grow from $12 trillion to $22 trillion, while Bitcoin's supply remains unchanged.

Institutional adoption: The approval of Bitcoin ETFs and the inclusion of Bitcoin in corporate treasuries have solidified its role as a store of value. For example, analysts like Michael Saylor and Cathie Wood predict that Bitcoin could reach $1 million per coin, citing institutional demand and fiat devaluation.

Macroeconomic Hedging: Bitcoin is increasingly behaving as a "high-beta, liquidity-sensitive asset," meaning it reacts strongly to expansions in global liquidity. As central banks inject more cash into the system, investors flock to Bitcoin to hedge against inflation and currency devaluation.

Arthur Hayes has repeatedly emphasized this theme, predicting that Bitcoin could reach $250,000 by the end of 2025. Similarly, analysts like Anthony Pompliano believe that as long as governments continue to print money, the price of Bitcoin will continue to rise.

Risks and Challenges

Despite the optimistic outlook for Bitcoin, it is not without risks. Policies that drive Bitcoin's growth could also trigger volatility.

Regulatory scrutiny: As Bitcoin's influence grows, governments may implement stricter regulations, potentially dampening demand.

Systemic vulnerability: If debt growth exceeds liquidity injections, it could strain the financial system, leading to abrupt market corrections.

Market dynamics: Short-term factors, such as a US government shutdown or fluctuations in the Treasury General Account (TGA), could temporarily reduce liquidity and suppress Bitcoin's price.

Nevertheless, the long-term trend is clear. As Hayes points out, "The operating logic of the dollar money market doesn't lie. Once you translate terms like 'SOFR' and 'SRF' into 'printing money' or 'destroying currency,' it's easy to see where the trend is going."

Conclusion: The Future of Bitcoin in a Debt System

The US financial system is caught in a cycle of debt creation and monetary expansion. Politicians prioritize short-term spending, the Treasury issues bonds to cover deficits, and the Federal Reserve ensures these bonds are purchased, even if it means indirectly printing money through tools like the Special Funds Regulator (SRF). This process devalues the dollar and drives demand for alternative stores of value.

Bitcoin, with its fixed supply and decentralized nature, is perfectly positioned to benefit from this environment. As global liquidity expands, Bitcoin's role as "digital gold" is likely to be solidified, attracting both institutional and retail investors. While short-term volatility is inevitable, the long-term trajectory points to continued appreciation.

For investors, the key is to monitor the mechanisms that create the dollar, such as the SRF and repurchase market dynamics. When the Federal Reserve intervenes to provide liquidity, it signals that the printing press is running and Bitcoin's bull market is thriving.

References:

U.S. Department of the Treasury. Fiscal Service. (2025, September 2).

Federal Debt: Total Public Debt (GFDEBTN). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED. Retrieved from

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GFDEBTN

CoinCatch Team

Disclaimer:

Digital asset prices carry high market risk and price volatility. You should carefully consider your investment experience, financial situation, investment objectives, and risk tolerance. CoinCatch is not responsible for any losses that may occur. This article should not be considered financial advice.